1/28/19

Listen to Dean Vlahaki, MD, MBBS, RDMS, FRCP, a member of the POCUS Assessment Committee from Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, talk about his experience with POCUS in Canada and how POCUS is benefiting the clinical environment.

Looking for additional inspiration? Sign up for our POCUS Post™ newsletter to receive monthly tips and ideas.

Transcription:

James Day: Hello and welcome to the Point-of-Care Ultrasound Certification Academy podcast where we focus on POCUS. Here, we will discuss all things related to point-of-care ultrasound; the practice, the trends and its impact on healthcare. Our program will engage thought leaders who are defining global patient care with the stethoscope of the future.

James Day: James Day here today recording live from the Focus on POCUS Studios. Today we have Dr. Dean Vlahaki as our guests Dean MBBS RDMS FRCP, graduated from the University of Queensland Medical School in Brisbane, Australia in 2011. He completed his emergency medicine residency training and POCUS specialty training at McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada in 2017. Vlahaki now practices at multiple sites and a network of academic trajectory care hospitals in Hamilton, Canada. He is also an assistant clinical professor at McMaster University and a major contributor to the emergency medicine Point-of-Care Ultrasound Fellowship program at McMaster University. How are you today, Dean?

Dean Vlahaki: Hi, good. Thanks for having me.

James Day: Thanks for being here with us. So I just wanted to know because a lot of it’s changing now, but when you attended the University of Queensland Medical School in Australia, did they have an integrated POCUS program in their curriculum?

Dean Vlahaki: Well, my exposure to point-of-care ultrasound was probably overall pretty limited in medical school. Knowing that I wanted to be an emergency physician and that I would complete ER rotations as electives in North America in order to gain a residency spot here, I used most of my time in Australia in the emergency departments to do more rural emergency medicine, where POCUS with limited. I did my clinical rotations in a place called the Sunshine Coast, which is about an hour and a half north of Brisbane by car. It’s really close to the big surfing Mecca, known as Noosa Heads, which is pretty well known in the Pacific. So I got to do my medical school on the beach basically.

James Day: That must have been terrible, man.

Dean Vlahaki: Yeah. It was pretty fun. I got to live in a house with an Australian and a few other Canadians and we had a blast. The majority of my training there in the emergency department was spent in an even much smaller town called Gimp. And in terms of my POCUS exposure there, it was pretty limited. They were only really doing basic applications, like fast examination and trauma. So it wasn’t till coming back to North America where I really started to learn more about advanced applications that I use today.

James Day: Wow. Life on the beach. So are you a surfer or a snowboarder or skier or anything like that?

Dean Vlahaki: My whole family, we really enjoy skiing. We pretended to surf. But really, I mean you’d have 10-year-old kids blasting by you on the wave. So we just pretended.

James Day: Yeah. Surfing’s hard ’cause you got to paddle through those waves. Much better to be on a ski lift, go up the mountain.

Dean Vlahaki: Exactly.

James Day: So beyond focused cardiac for chest pain or right upper quadrant scans for abdominal pain, what are the other most frequent POCUS scans you’re seeing in your ERs?

Dean Vlahaki: So as an emergency physician at Hamilton, as you mentioned, I work in a network of three hospitals plus two urgent care sites. We, as a family, have two small children at home. They’re three and one. They keep, my wife and I quite busy, so we had decided that I would do pretty much essentially night shifts only, which I like quite a bit. In Canada, and certainly locally and here in Hamilton, we don’t have access at all, essentially, to formal radiology, ultrasound, overnights, unless you call the ultrasound tech in from home.

Dean Vlahaki: So point-of-care ultrasounds, really quite useful for myself in that way. Generally, I’m using point-of-care ultrasounds to do hemodynamic studies, like cardiac and DVT, but really the most common ones I do are renal ultrasound for suspected renal colic, early pregnancy to diagnose intrauterine pregnancy and assess for ectopic pregnancy and right upper quadrant scans to assess for colicystitis.

Dean Vlahaki: I do also, quite frequently, look for abdominal aortic aneurysms, but this would be all times a day and not just overnight.

James Day: So renal, with kidney stones, is usually late at night like that?

Dean Vlahaki: Yeah. We have a very large urology population here in Canada. It’s actually one of the, in Hamilton anyways, one of the largest sites for urology, I believe nationally here at Saint Joseph’s hospital, so we have quite a large number of renal colic patients and of course kidney stones, they tend to come back too, so it’s a very common presentation to our emergency departments.

James Day: Can you tell us about the training at the fellowship program at McMaster’s University, which is very famous globally? McMaster’s University.

Dean Vlahaki: Yeah. It’s sort of known as being one of the homes of problem-based learning and sort of got its name that way. It’s also fairly well known for research, just in general and evidence-based medicine as some of the founders of evidence-based medicine grew a name for themselves here.

Dean Vlahaki: Our fellowship program is really called a Royal College Area Focus Competence to be most accurate, but it’s easier to just call it a fellowship. It’s certainly one of the most robust in the country and probably in North America, I would think. It’s a one-year-long learning experience based at St Joseph Hospital in Hamilton and we generally take two fellows per year. There’s a really heavy clinical component, ’cause as I was mentioning earlier there in the department when we don’t have access to radiology ultrasounds, so usually it’s evening and nights mostly.

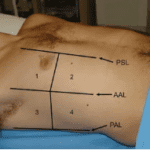

Dean Vlahaki: Basically their role is to perform point-of-care ultrasounds when ordered by the treating physician, just like any other test or imaging or medication order. They, over the course of the year, have to complete a minimum number of scans in each category such as cardiac, DVT, soft tissue, abdomen, and so on. And they also complete quite a broad spectrum of advanced applications like scrotal ultrasound, head and neck and ocular, among other things. We archive all of our images and studies in a cloud-based software so that these fellows can review with any of the ultrasound staff either remotely from home or from a different hospital.

Dean Vlahaki: So, typically these fellows complete over 2,000 scans annually. And I completed the fellowship here approximately three years ago, which is how I landed my job here now. Certainly, I think the program is a real benefit to our patients because we essentially have a physician who’s a senior resident in the hospital dedicated to performing point-of-care ultrasounds, only for that reason. That’s why they’re there. So I think it’s a really successful program, and we do actually allow applicants from all locations. So if anyone’s interested, look us up.

James Day: When did you get your RDMS? How long ago was that?

Dean Vlahaki: That was right at the end of the point-of-care ultrasound fellowship. Originally, the goal was to build to that certification, but more recently the Royal College of Physicians in Canada has recognized the area of focused competences being a certification in itself. So we’ll see if the fellows still continue to obtain that.

James Day: Yeah. All right. How about two questions? We’ll play a game here. Two questions here, for some of the pearls, pitfalls, and the more controversial POCUS topics. So I don’t want to ambush you here, but here you go. So what is the best anatomical approach for ultrasound needle-guided pericardiocentesis?

Dean Vlahaki: This is a good question actually. I completed one of the only handfuls of these that I’ve done just a couple of weeks ago in a patient with lung cancer and a new malignant pericardial effusion with a pretty impressive tamponade.

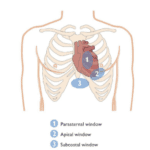

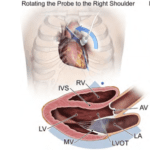

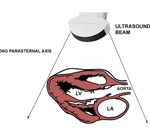

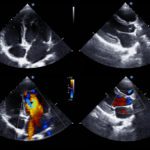

Dean Vlahaki: I completed it with an ICU colleague of mine, who also does emergency medicine, who happened to be in the department at the time named Dr. Julian Owen, who is quite good with point-of-care ultrasounds himself, and honestly it’s a bit of a hedged answer, but it’s really the best window you have, to see that big pocket of fluid. Generally for me, I think this is a parasternal approach and typically the best way to do this is to, I think, is to landmark the parasternal area with the largest fluid pocket and have a second set of hands to look from the subcostal location, so you can have real-time needle guidance, and see the needle go into the pericardium. Of course, you always want to do a bubble study with agitated saline to confirm you’re in the pericardium and you definitely don’t want to injure or puncture a cardiac chamber.

James Day: Right. I kind of remember the old school, where they hook an EKG up and they look for, oops, maybe I hit the myocardium and there’d be an ST elevation.

Dean Vlahaki: Yeah, I’ve definitely seen that done before in the ICU. We have quite a large post-cardiac surgery ICU, at our site as well, but certainly, if you can see the needle, I think that’s a much better approach.

James Day: Way better, way better. How about evaluation for right ventricular function on point-of-care ultrasound, that helps us decide whether or not to thrombolysis a patient, let’s say with a submassive pulmonary embolism. What are your thoughts on that?

Dean Vlahaki: Yeah, I think this is another great question. Locally, we’re very fortunate to have a really internationally renowned thrombosis sub-specialty program.

James Day: Oh Wow.

Dean Vlahaki: Yeah. Locally, we produce quite a large amount of very prominent research that is that they’re considered to be sort of thought leaders in the field. Certainly, I don’t do any of that specifically, but we have on-call 24 hours a day, thrombosis specialists that can help guide us with these kinds of decision-making issues.

James Day: That’s excellent.

Dean Vlahaki: Yeah. Generally, here, I find, they are very conservative with thrombolysis as a whole and prefer to treat with things like low molecular weight heparins as a bridge to catheter-based thrombolysis, or thrombectomy later, by interventional radiology. Having said that, I have definitely thrombolysed a handful of patients in the last year, to two years. Generally, they are too unwell to go for definitive imaging and are too unstable to wait for any further therapy. Luckily for me that the times that it has been performed, they’ve been successful. And particularly I find this to be successful in patients who are pregnant and also exposing them and their fetus to the radiation associated with a CT scan would potentially lead to further harm. Point-of-care ultrasounds, great from this perspective because you can make the diagnosis at the bedside and also monitor her response to therapy with regards to RV strain right at the bedside.

James Day: Wow. Okay. I can’t stump you, man. Those are all very good. How about if I throw another one out here?

Dean Vlahaki: Sure.

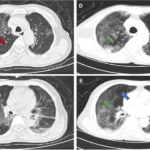

James Day: Before we go here. How does a point-of-care ultrasound for a pneumothorax compare to a chest x-ray and CT?

Dean Vlahaki: So, x-ray and CT are good if the pneumothorax is there. I predict, well I should go back. X-ray is good if the pneumothorax is there and visualized, but it’s not a good rule-out test, particularly in our trauma patients that come in on a backboard and are laying supine. So ultrasound is a much better test in this regard and there are better diagnostic parameters, for sure. I guess the question is if you don’t see a pneumothorax on a chest x-ray, is it large enough to be significant anyhow, or could it wait until definitive imaging later? Certainly, patients that are unstable might benefit from a bedside thoracotomy, to decompress the pneumothorax and there has been a couple of cases in the last year where I have done that and it has made a big difference.

James Day: All right, Dean, listen, all good stuff, man. And listen, I want to thank you for taking the time to be here on today’s show. I also want to thank the audience for listening and don’t forget for even more POCUS talk, you can follow us on Twitter at POCUS Academy and on Facebook at POCUS Cert Academy. Dr. Vlahaki, it was an honor to have you today on our podcast and I thank you so much.

Dean Vlahaki: Thanks so much for having me.

James Day: All right then. Bye.

Dean Vlahaki: Bye.

James Day: We hope you enjoyed today’s podcast. Focus on POCUS. Be sure to tune in with us next week for more interviews with thought leaders that are at the forefront of global point-of-care ultrasound.

James Day: The thoughts and opinions expressed in this podcast are the views and opinions of the guests and not those of Inteleos. This podcast is for information purposes only.